Closure Blooms

I tried to kill myself at Yale University when I was a student there 51 years ago. Returning to the 50th Reunion of the class of 1966, the class I didn’t graduate with, I sought closure to what has always been a painful experience. A friend from those undergraduate years invited me to come. I was reluctant, but he said it would be good for me. Relenting after several invitations, I decided this was an opportunity to find peace with what were not, as the Yale’s college song begins:

“Bright college years, with pleasure rife,

The shortest gladdest years of life…”

My time at Yale was not happy. I did manage to graduate two years later in 1968. Living off campus, I spent my time in the Art and Architecture school and never again set foot in my former resident college. I knew no one in the class of 1968, whose most famous member was George W. Bush. I am not considered a member of the class of 1966, nor do I feel like a member of the class of 1968. While at Yale and afterwards, I never thought I belonged.

The feeling of alienation began the first day I walked onto the freshman commons. I had been accepted on the waiting list because, I figured, the Davis family had numerous men who attended Yale. My grandfather was in the class of 1914. His brother graduated in 1907. My father was in the class of 1943, but he never graduated. His failure put pressure on me to uphold the family tradition. I didn’t want to attend Yale, but my SAT scores were not good enough to get a scholarship to Northwestern, where I wanted to go. The family decided the university was too expensive and would not fund me. So I was confronted with the choice of going to a school that was my last choice or going into the Marines. I was leaning towards enlisting. But Yale accepted me, and the family said they would support me. I thought I was stuck. Go where the family wanted me to go, or go into the military and likely end up dead in Vietnam.

Everyone I met a Yale seemed so much smarter than I was. They were class valedictorians, had extraordinary talents, and spoke numerous languages. I had no known talents, nor did I really know what I wanted to do with my life. I fantasized becoming a writer, but that idea was soon crushed. The privilege of an Ivy League university didn’t seem so wonderful to me.

In the freshman dormitory up in the fourth floor double room, I struggled with all my classes. Foreign language training was required. I took French, but I couldn’t seem to retain or understand the language. I spent hundreds of hours in the language lab, only to go to class unable to comprehend what the teacher was saying. Decades later, I learned why. I am dyslexic with sound comprehension one of my minimal brain malfunctions. I barely passed the first year of two required years of a foreign language. The second year I failed.

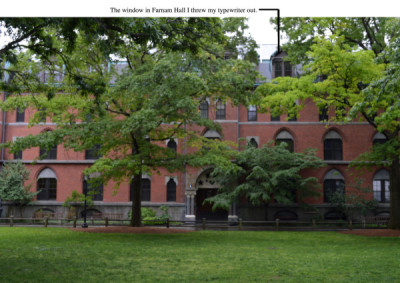

All the other courses required writing papers. English class was hardest of all. Weekly and sometimes daily essays were required. I had a Smith Corona manual typewriter, and had taken one class after high school to learn how to use it. I wasn’t very proficient. At my desk looking out the fourth floor window onto the commons, I tried to type the required papers, but the effort was totally frustrating. I was slow and could only hunt and peck letters, but even worse, words would come out backwards. The word “the” is common in English, and seems to exist in almost every sentence. When I typed it, “the” came out “hte” again and again. I would get out the white out, blank out the mistake, and type again, concentrating hard to get the word right. “The” continued to be “hte.” Gradually I became more and more enraged as I stared out the window into the late night darkness of the commons. Unable to control the mounting anger, I threw open the window, picked up the typewriter, my sheet of typing still in it, and tossed it out the window.

After sitting in my chair until my rage abated, I thought “Well that was stupid.” I went downstairs and out into the grass to search for the typewriter, which I found slammed into the earth, its carriage wracked. I bent it back into the rectangular shape. All the keys worked, except for the “W,” which was permanently wrecked. I didn’t try to type my papers after that. I hand printed them, and got crummy grades because a Yale student was expected to hand in typewritten essays. My fantasy of becoming a writer withered.

Poor grades, drinking, and violence (I put a fire ax in door at a party in a drunken state on a dare), was my undergraduate history. Too much family pressure to succeed where my father had failed followed me around the campus. Too much emotional pressure haunted my travels on the streets of New Haven. My father, a handsome man and womanizer, whom his classmates called “Cock,” for his sexual attraction, married a gorgeous local nightclub singer and was thrown out of Yale. You could not be married and attend the university before the Second World War. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps when the war began, and the family would not support his return to Yale as long as he was married to my mother. He never did return. His marriage ended in totally acrimony.

At five years old I was taken from my mother’s sister’s house in New Haven, after my mother had run away with me to avoid giving me up to the Davis family. I was made a ward of the court and placed in a foster home, and I never saw nor heard my mother’s name ever mentioned again within the family. But I was warned that if she confronted me on the streets of New Haven, I was to rush away because she was an evil woman. Yale and New Haven were hell to me.

By the middle of the junior year, I was failing all my courses. I was drinking heavily. My roommates wanted me to move out because I was acting so weird. One drunken evening, I cut off my left index finger at the first joint while playing with a jackknife.

Rushed to the hospital, the finger was sewn back on, but I was forced to go live by myself in a garret room up a narrow coiling stairway on the top floor of an entry tower. I felt like an exile. There on an April night in 1965, I took 150 aspirin tablets and gulped down a bottle of scotch. When the world started to spin, and a roar began in my ears, I called for help from a friend. He came with the campus police, and I was rushed to the hospital. My stomach was pumped and I narrowly survived the night. I pleaded to live as I listened to the death rattle of a man in the bed next to me.

My undergraduate campus life at Yale ended. It was the best thing that had ever happened to me. After a short stay in the mental ward of Yale New Haven Hospital, I moved into a community residence called Rochedale and found a job. I discovered there was a whole world beyond Yale, and I found things I was good at. Art and design became my life once I graduated from Yale and the Yale School of Architecture. I never returned for many years.

My daughter, without my encouragement went to Yale, graduating in 2000 where she thrived. I came back for her commencement. By then I had grown to appreciate the education I received at the university, but I never loved it, nor did I yet feel I belonged.

These feelings changed when I returned to the 50th reunion. I walked around the campus, looked at the freshman dormitory, Farnam Hall, where I had thrown my typewriter out the window, and laughed. Will Farnam, once my roommate and the person who invited me to come to the reunion, is descended from the man for whom this dormitory was named. Will has an even longer family connection to the university than I do. I walked along the street and looked up at the little window in the garret room where I had tried to kill myself. It no longer had any emotional connection for me. I saw the campus in a new light. It is a beautiful place to get an education. The buildings have stood the test of time and look attractive. The campus is filled with pleasant walkways lined with lovely green trees.

I made a special journey to the one place I have always been fond of at Yale. The Elizabethan Club was where I went for respite from the disappointment I felt as a student. Many afternoons I would go the club, have tea and cucumber sandwiches, sit in one of their comfortable chairs amid the books on Shakespeare and the scholars and students who loved literature, and look at the cartoons in the English periodical Punch. Having my tea and a tuna fish sandwich -– cucumber sandwiches are now only available on Thursdays -– I recalled why I liked this place so much. One met all kinds of interesting people and engaged in conversations that extended way beyond mother Yale. On my brief visit to the small frame house, I met a recently-graduated student who is studying to be a doctor at the University Hospital in Rochester, New York, and recently returned from an extended visit to Africa, and a man who graduated from Yale in 1976 and lives in London. He is a retired banker who recently wrote a book on the economics of Mohammed. We talked about the vagaries of book publishing.

Amidst the tables under the reunion tent, I reconnected with the few men I knew from the 1960s, who came to the event. Will Farnam came with his partner Cal. They are a good-humored couple. Cal enlivened these square and elderly gentlemen with his light-up rhinestone metal hat with fur around the brim. Paul Anderson, also once my roommate, was there with his sweetie of twenty years. He had a career as a high school teacher. We recounted amusing stories of one another. I recalled how once, dressed only in “whitey tighty” underwear while wearing a cowboy hat and with two six shooters strapped to his waist, he threatened to shoot our neighbor for partying too loudly. Duncan Campbell married a Native American woman. He lives in Colorado and operates a community radio program that conducts dialogues, not interviews, with significant cultural and spiritual leaders. Peter Lowndes is an actor and writer from LA, who trained me in the art of public presentation, but I had lost contact with him for more than a decade. Doug Knott is an LA performance artist. We have been friends a long time, but Yale seemed unimportant to our relationship. I realized that I treasured these few with whom I had a sense of comradeship.

I met some Yalies I did not know before the reunion. Rob Kinney III is a man who loves music and had a business career before giving himself to his avocation. His eyes sparkled, and we talked about barbed wire, a material I have used to make art, and the product his great-grandfather invented. Many had family histories with the university. I realized and could appreciate the fact that the Davis family was connected to Yale through the entire 20th Century from my grandfather’s brother in 1907 to my daughter in 2000. These graduates had names like my own, family names that they were stuck with. Given my own history, I hated my name, Carlton Morris Davis, Jr. What I saw were many IIs, IIIs, and juniors; these men had to find their own paths out of WASP names. I found empathy for them, and I found acceptance of my own circumstances. I found I belonged, and I liked the people I belonged with. Yale has become a cherished part of me. Closure has bloomed.

The Freshman Commons, Yale University